Since 2023, artistic swimming has undergone significant changes in its global regulations. International competitions have experienced a period of adjustment, with frequent updates to address challenges in interpreting and applying the new rules.

Many countries have since adopted these new regulations at the national and regional levels. However, that has also come with its own sets of challenges, particularly in younger age groups, where some of the system’s limitations became more apparent. While older national team athletes have largely adapted to the push for higher Degrees of Difficulty (DD), younger swimmers often struggled to meet these demands.

In response, a few countries and regions have taken the liberty to tweak and modify the rules to better suit their athletes’ needs. Catalonia, Spain, and Switzerland, for instance, have adjusted the regulations to align with the skill levels and long-term development of their artistic swimmers, especially in the lower age groups.

Catalonia: Focus on Progressive Development and Mastery of the Basics

Damia Palmer, president of the artistic swimming section at the Catalan Swimming Federation (FCN) and Spanish official, explained that the main goal was to create a system that aligned with the capabilities of younger athletes, specifically those in the Under 10 and 12 years old categories

Both in Catalonia and Spain, numerous officials and coaches from top clubs, such as Bet Fernandez of C.N Kallipolis, heavily contributed to the development and implementation of this modified system. Finding a way to better accommodate these age groups had become a growing concern of theirs.

Ultimately, Catalonia took an innovative approach by modifying the difficulty tables for the younger categories. For example, U10 athletes compete with new, specially-designed levels—Level 00 and Level 0—that are absent from international guidelines. For this age group, the difficulty limit is also set at Level 3, which, on top of it, can only be achieved by the older swimmers within this category.

There are also limits on the difficulty levels and the number of times each movement can be done. For example, athletes who are between 6 and 7 years old (Benjami 1 in the table above) are limited to the levels 00 and 0, and can only do three movements from each family.

These modifications ensure that these younger swimmers can perform movements that they are physically capable of, while progressively mastering fundamental techniques without the pressure to attempt advanced skills prematurely.

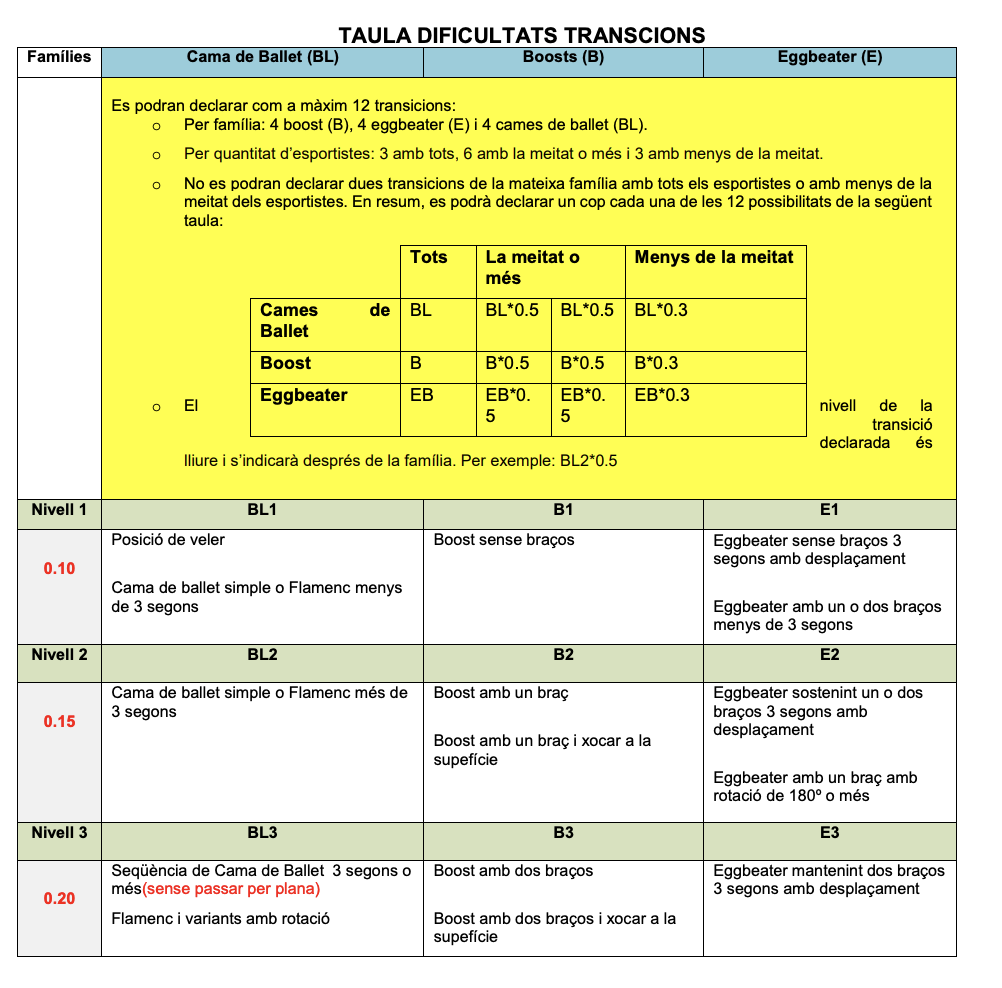

The Catalan federation has also introduced a table of transitions, where teams can declare what are considered transitions, like ballet legs, boosts, and eggbeater, at the international level (and thus without any difficulty value). Each family of transitions receives a single score.

This streamlined approach fosters gradual progression in this U10 category, where transitions make up most of the routine either way, while prioritizing technique and foundational skills.

Finally, Catalonia has opted for a gentler approach in relation to basemarks by only removing the family not well-executed from the total DD, rather than downgrading the entire hybrid. This method ensures that these younger artistic swimmers can still benefit from a learning curve without the demotivating effects of harsh basemarks. Similarly, the penalties for synchronization errors (SE) have been modified to be a bit more lenient.

All in all, Palmer’s philosophy centers around flexibility and adaptation: rules should not be static and should evolve to serve the athletes’ needs at the local level. By guiding younger swimmers through structured, achievable goals, the Catalan federation aims to balance ambition with responsible athletic development.

“Feel free to adapt to your reality and help push everyone towards the path you think is correct,” he said. “You can adapt to each age group and aim for progression, especially for the younger swimmers. It’s very important to encourage other federations to adjust to their own levels, to their reality in their regions or countries.”

Spain’s Broader Approach: Fostering Innovation and Artistry While Setting Limits

The progressive strategies introduced by Catalonia have also influenced broader changes at the Spanish level and in all national championships last season.

In the U12 category, the Spanish federation (RFEN) implemented similar requirements and limits on the difficulty levels for acrobatics and hybrids, including a maximum cap on the DD of each free hybrid. Once again, this measured progression ensures that young athletes are not overwhelmed by routines that are too complex for their current abilities.

For example in a U12 duet routine, a free hybrid can not have a DD higher than 3.0. All families from the difficulty table must also be shown – respecting the appropriate restrictions on levels and repetitions -, and a few transitions are also required: one boost with one or two arms, one eggbeater sequence with one/two arms up (minimum 5 moves), and a sequence with at least two different ballet/flamenco/double legs.

The federation also introduced “Creative Hybrids” for routines in the U12 and Youth categories. At first, coaches could only declare bonuses – meaning pattern changes, synchronization, traveling and placement – and a connection from the difficulty table for this hybrid.

It has evolved over the course of the season: Now, nothing is declared (neither families nor bonuses) and its default DD is 1.0, giving all the value to the execution scores and looking for its contribution in artistic impression.

The creative hybrid has been well received in Spain, offering a blend of freedom and structure that promotes artistic expression within a framework that prioritizes safety and technical development.

This specific hybrid became a mandatory Element in all U12 routines, as well in the team and free combination routines for the Youth age group.

Example of a Creative Hybrid (as per the first definition, based on bonuses-only and a connection):

Finally, Spain also reduced the number of Elements required in certain routines. For example, in youth solo, the number of hybrids has been decreased from six to five, and five to four for the U12 soloists. This allows for more time for transitions, and for a more focused performance where quality is emphasized over quantity.

Such adaptations, with only the major ones listed here, align with Spain’s goal to encourage athletes to execute elements at a higher standard, rather than attempting to perform more difficult routines that may compromise their overall execution.

“If you want to progress, you can’t have 4 in execution, even if it is worthy for the results,” Palmer added. “But we, at the federations, have to understand that coaches are doing what they can to win. It’s not a solution to simply ask them not to use all the tools they have, or to take it easy. It can’t be an individual decision; we must force them to slow down for the good of the athletes. We need to implement rules that are constructive for everyone, and not be scared of doing that so that there is real progression for the athletes, especially at the lower levels.”

Find out more about RFEN’s adaptations in this document.

Switzerland: Prioritizing Athlete Well-Being and Technical Foundations

In Switzerland, the approach taken is fairly similar and rooted in the well-being of those younger athletes. Valentina Bogacheva and Michelle Nydegger, respectively official and performance chief at the Swiss Aquatics Federation, are at the forefront of the country’s efforts to implement their own adaptations.

Nydegger further insisted on the federation’s role in managing the new challenges that arose with the new system:

“The side of the coaches is understandable—they all push each other higher. So, it’s up to us to create a system that doesn’t enhance that, one where we can prevent ambition that is too much for the athletes. It’s not fair to put the responsibility only on the coaches. We need to take care of that and set limits.”

Restrictions in the lower age groups were hence implemented to curb overly ambitious coaches that pushed young athletes beyond their capabilities. As Bogacheva noted when observing the first few competitions under the new system, “it was like we started to run before we had the ability to walk.”

To protect the physical and mental well-being of the swimmers, it became urgent to act. Much like in Catalonia and Spain, specific adaptations were created for the U10 and U12 categories, with a focus on guiding coaches to prioritize fundamental skills and execution.

For example, limitations were set up on each family of movement and their respective levels of difficulties. It also became mandatory to have each family represented as well, and not only show the higher-valued ones like Rotations or Flexibility. Additional requirements were added, like showing a fully synchronized hybrid, pattern changes, etc. In the U10 age group, a few more basic movements and transitions, like ballet legs, are obligatory as well.

“The coaches shouldn’t rush and forget about technique,” Bogacheva said. “At this age, [the athletes] need to know what a vertical position is before trying to make a twirl. It’s the gradual steps that they should go through. It’s also really important for us to have nice choreography, and not just rotate, rotate, rotate. We would like to keep creativity in our sport. We want to give the coaches the chance to still be choreographers, and not just calculators.”

The requirements serve to ensure that the athletes learn to execute all different types of difficulties and encourage the use of different tools of expression when creating choreographies to strengthen the artistic impression of routines.

Over the last few months, the Swiss federation has continued its work, and built a full system of rules in relation to the new DDs for U12 and U10, and introduced some transition recommendations.

Read more about the limitations and guidelines for the U12 and U10 categories in Switzerland.

Read more about further adaptations for the U10 category.

Common Ground: Adapting for the Future

Federation officials in Catalonia, Spain and Switzerland all share a common philosophy: the need to adapt the new artistic swimming rules to better fit the developmental levels of their athletes, while promoting long-term progression.

By taking a more thoughtful and tailored approach, they are encouraging a broader vision for the future of artistic swimming. They are reminding the world that fostering young talent involves more than just pushing boundaries and asking for high difficulty; it requires nurturing athletes with a holistic approach that values health, technique, and creativity.

With the regulations set to change yet again for the upcoming 2025 season, these federations and officials will nonetheless continue to find ways to adapt in order to ensure long-term success and longevity of the sport domestically.

ARTICLE BY CHRISTINA MARMET

Cover photo: Giorgio Perottino / Deepbluemedia

If you’ve enjoyed our coverage, please consider donating to Inside Synchro! Any amount helps us run the site and travel costs to cover meets during the season.