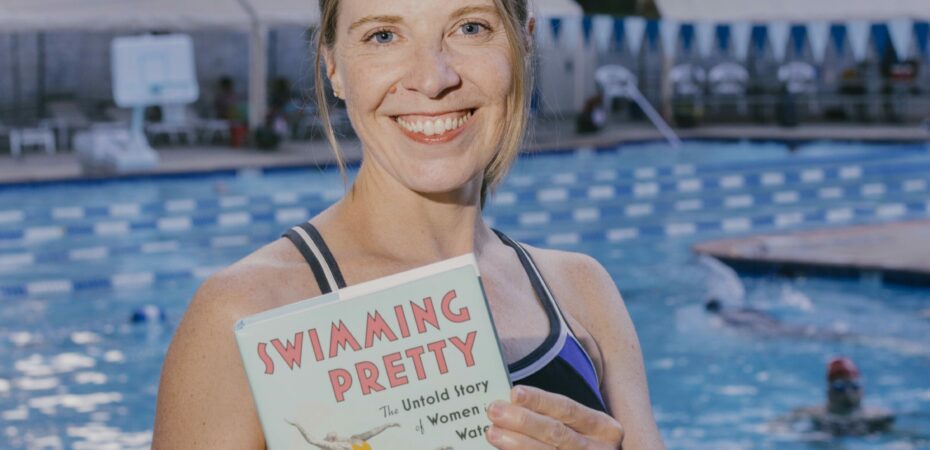

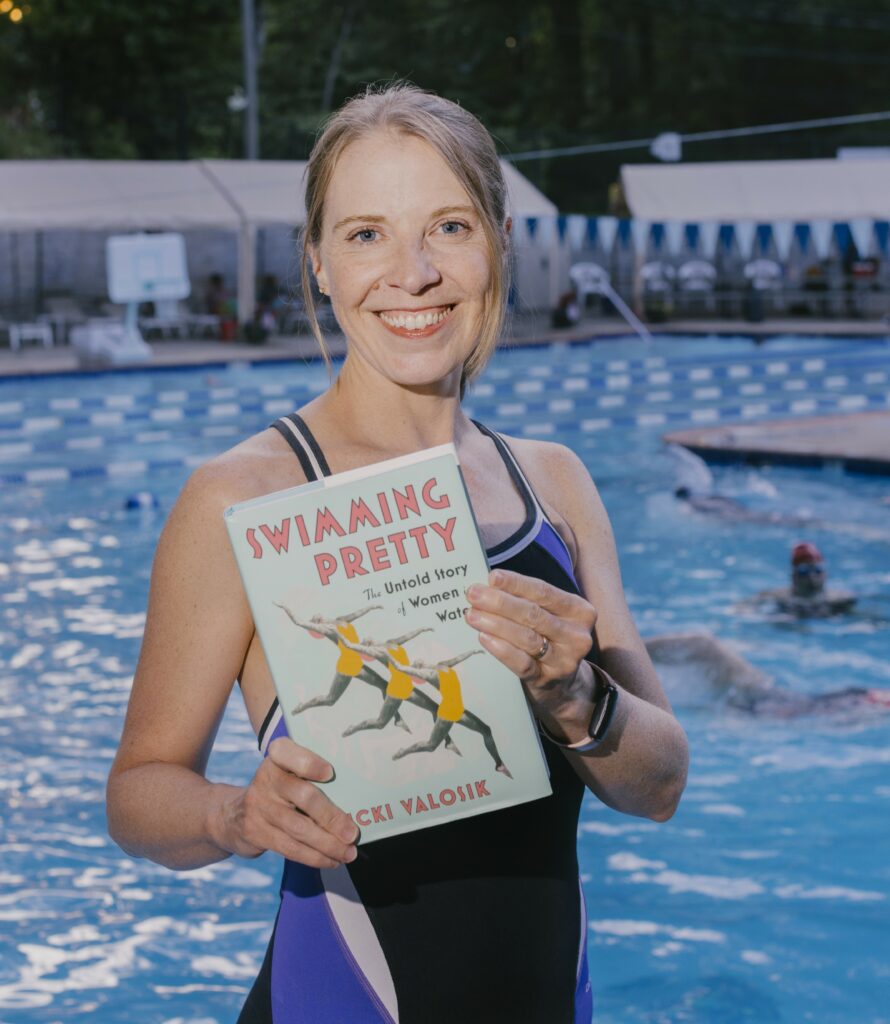

Vicki Valosik is the author of “Swimming Pretty: The Untold Story of Women in Water“, a book released earlier this year that traces the unique history of artistic swimming—from the origin of some of the basic moves still done today through to the modern Olympic arena.

A journalist and writing teacher at Georgetown University in the U.S., Valosik first discovered the sport around her 30th birthday and quickly became a passionate masters competitor.

What began as a piqued interest for the origin of some of the moves she was learning eventually turned into an eight-year research project. To get to the bottom of it all, Valosik combed through countless archives to uncover the evolution of synchronized swimming, all while interviewing current and former athletes, coaches, and other key actors in the development of the sport.

In Swimming Pretty, she brings together stories of scientific swimming in the 1800s, lifesaving drills, water ballets, Esther Williams’ influence, and the competitive sport we know today.

Inside Synchro: How did the idea of writing a book on the history of artistic swimming come about?

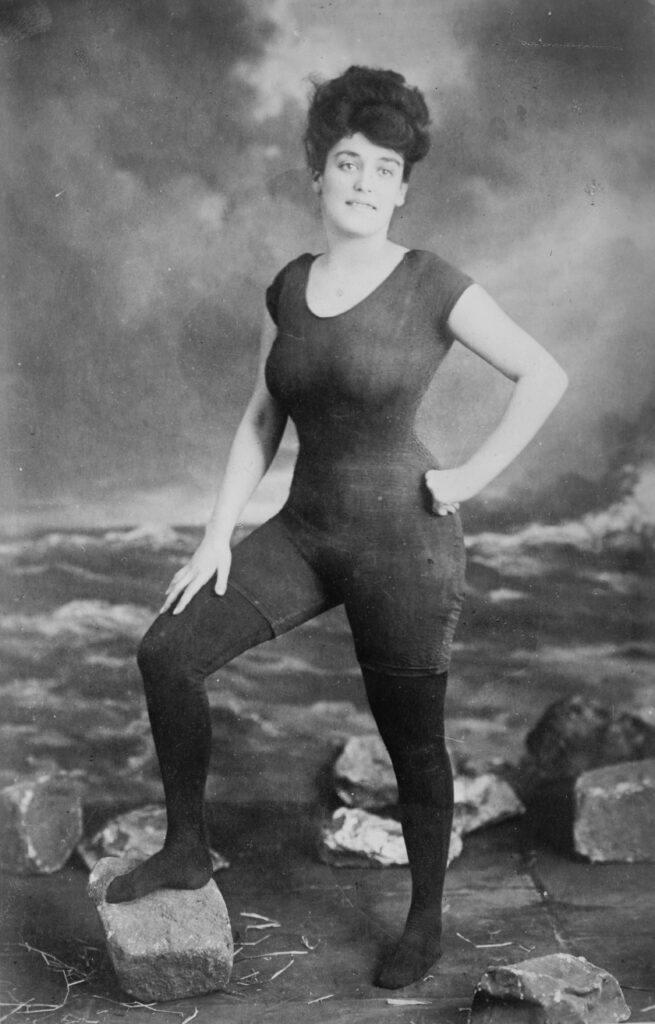

Vicki Valosik: I only really knew about Esther Williams. As I started researching, I very quickly learned about Annette Kellerman, who was so fascinating. She was an Australian competitive swimmer in the early 20th century who became a vaudeville sensation for her water ballet moves. But I also found that Kellerman is where most of the histories stop or start. So I wondered, where did she learn her moves? Then I learned that there were women doing this before her in the 1800s. Again, where did they learn their moves? And so on.

It really became an origin story: how did synchronized swimming originate and develop into the sport we know today. I was really interested in getting to the foundation of the moves, and then figuring out how they eventually came together with groups, music, and all of that to become what we know today.

I realized it was a good story when I started seeing all these connections to women’s empowerment, and how these performative styles of swimming gave women an entry point into the world of sport. This was really fascinating.

I was also really interested in the tension between performance and sport, beauty and strength in the water. For example, I write in the prologue about the time I had to swim without goggles the first time. I thought this was just crazy, because this is basic sports equipment and we’re athletes. Why would we make everything harder and not use goggles? But then, you know, this sport is also aesthetic, even though it’s incredibly athletic. It’s always been so connected.

I saw those same tensions through history when I was researching. Esther Williams dealt with this as a speed swimmer and as a performer in the water. So did Kellerman, and all these other women. It was something I really wanted to explore.

IS: In the book, it indeed seemed you really appreciated Annette Kellerman and everything she did, not only for the sport but also for women.

VV: Yes, Annette Kellerman was amazing. Some people call her the mother of synchronized swimming, and again, I was like, why is that? People were doing these moves before her, so why her? Now, I think it’s largely the way she applied dance to it, like it shows in the image in her book of her doing the pointed toe.

She’s noteworthy for so many reasons besides just being the first woman to do these moves and helping to popularize them. She was also a diver when women were barely swimming, let alone diving. And then, she escalated that to crazy high dives, swimming with alligators in her movies, etc. In all of that, she achieved incredible fame, and was the highest paid performer in vaudeville.

Really, her biggest thing was that women needed to get out and exercise. They needed to swim. They needed to stop wearing corsets and those horrible bathing costumes. Kellerman was one of the first women to wear a one-piece bathing costume, which was controversial at the time, and inspired others to follow her example. She used her platform every single chance she got and did a lot to advocate change for women. She showed that women were capable of so much more than people thought they were.

I didn’t know such themes were part of the sport’s story when I first started researching. Then, I really gravitated towards them. I have a master’s in sociology, and I very much identify as a feminist, so to see those threads was just really appealing to me.

It was really exciting to see Annette Kellerman and these other women challenge the ideas about what female bodies could do, as well as what women could do at such important political times, with the movement for women’s suffrage building in the U.S.

IS: Was there one specific anecdote that you didn’t expect to find in your research, or one that you particularly liked?

VV: Oh, there are so many, it’s hard to choose one… One of my most favorite people while researching turned out to be Commodore Longfellow, who appears in the life-saving chapter. He was a water safety instructor, and founder of the American Red Cross Lifesaving Corps. I want to give props to him, he was just really so supportive of women in a time when society wasn’t.

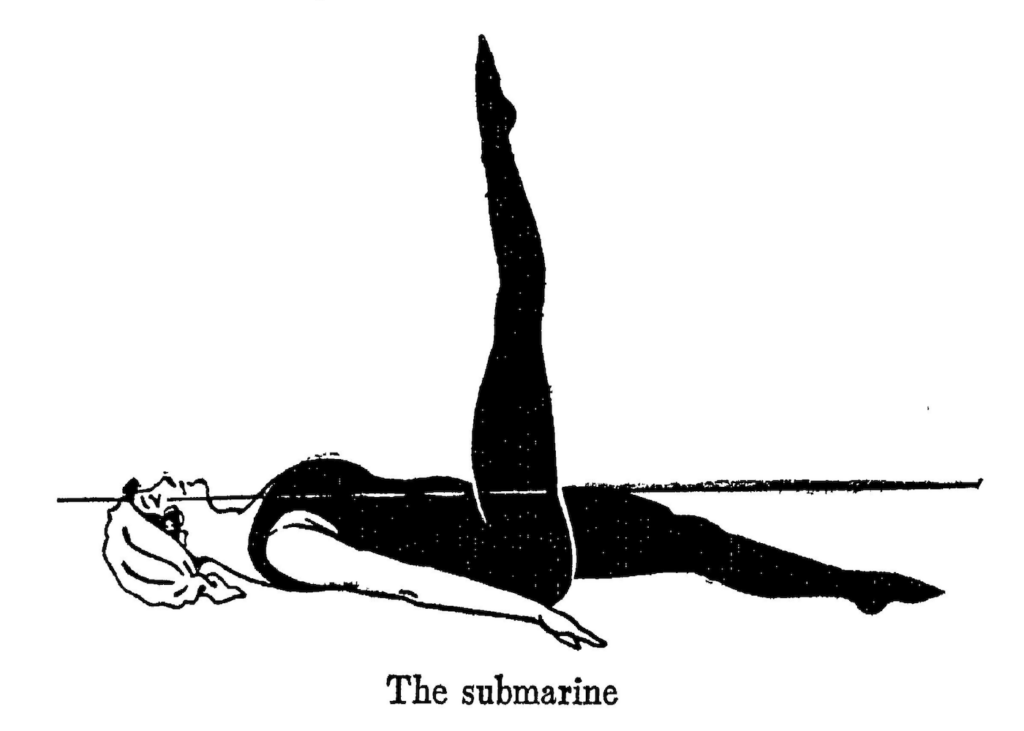

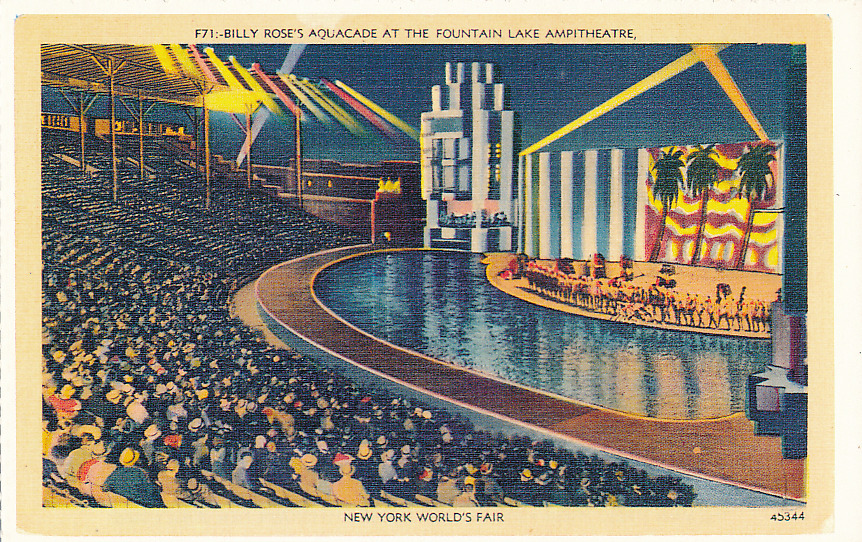

Commodore Longfellow believed that the best way to interest the public in swimming was to put on a good show. So, he had the idea of doing water pageants, which merged the theatrical elements of dialogue, costumes, and colorful set designs, with aquatics. His pageants featured demonstrations of various strokes, aquatic stunts, and lifesaving techniques.

So thanks to him, not only did generations of Americans learn how to swim, but the pageants were also really an early platform for synchronized swimming.

IS: At the start of the book, you discuss scientific swimming and how the first moves of our current sport were originally done by men. Overtime, as we know, the sport became virtually women-only. Can you go a bit more into this?

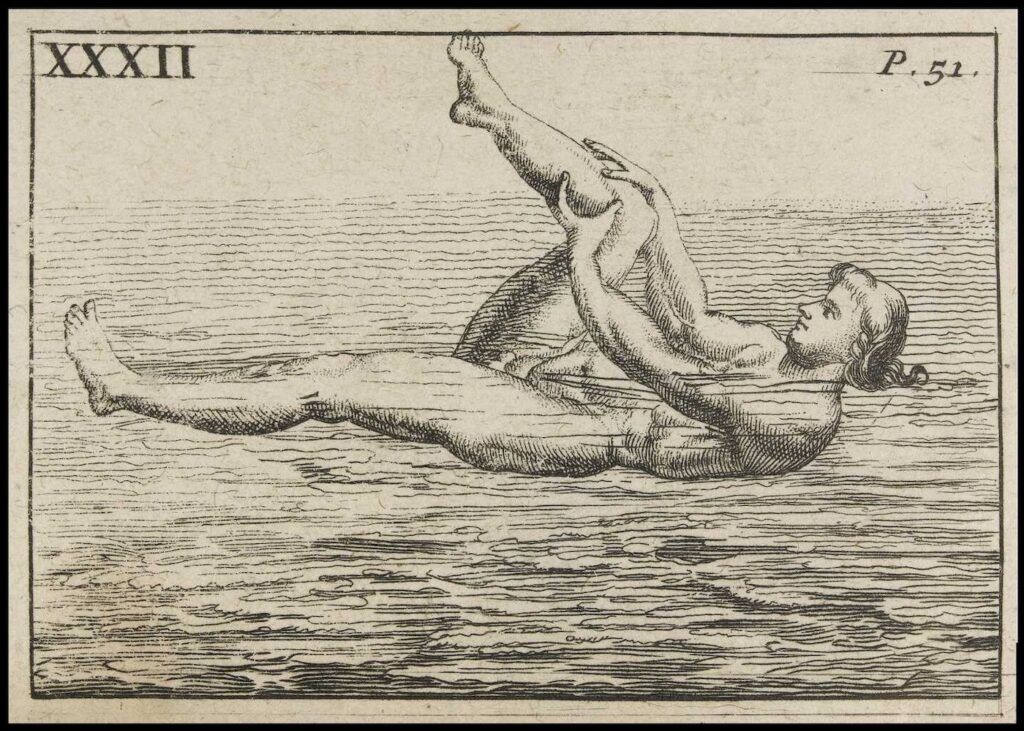

VV: Like you said, the first practitioners of the moves that would eventually evolve into synchronized swimming were men, including Benjamin Franklin! These “scientific swimming” moves, as they called them, were being done by men all the way back in the 1600s. All these years, women were strictly restricted to bathing, if anything, and it took a long time for that to change and for them to be allowed to swim. When it did, women were accepted as performers largely before they were accepted as swimming athletes.

In the 1920s and 1930s, there were particular ideas about what women’s sports and physical education should be. Sports for women should be collaborative, appropriately feminine, graceful, and not too competitive. There weren’t a lot of sports for women to join in at the time, so all of that created a great place for synchronized swimming to thrive.

Men didn’t need that. They had varsity swimming, endurance competitions, speed competitions, and much more. It was one opportunity that was there for women when men had a lot of other ones. So, it grew into a women’s sport, even though the first competition was co-ed.

Eventually, you also had the Esther Williams movies. She was considered the most glamorous woman, and here she was, swimming in the water and popularizing the sport. There was also the Billy Rose Aquacade, and all these other showgirls-types of entertainment that displayed hyper-feminized synchronized swimming.

On top of that, there just wasn’t that much interest from men anymore. Well, there were barely any men doing it at all from the beginning, and then they dropped out. So because of all these different factors, it overall prospered as a sport for women for a long time.

Then, the trends started changing the other way. Of course, Bill May was a major pioneer and fought tremendously. People also fought for him in the late 90s and early 2000s, but then that didn’t happen for various reasons as I write about in the book. Now, we’ve been seeing major changes and openings for men. Hopefully in LA 2028, we will see men in the Olympics.

IS: Do you feel like this hyper-feminine image of the sport over the course of history has also made it difficult for people to take it seriously?

VV: Yes, but thankfully I feel like it is changing organically. When it became an Olympic sport in 1984, it was treated horribly by the media. All of these male sports writers came out of the woodwork once they saw it in the Olympics and wouldn’t understand how hard it was until they were challenged to try.

There was also the Saturday Night Live skit, which was taken with good humor by the synchro community at the time. But I found this article with Harry Shearer, one of the two actors. He actually said his intention was to mock the sport because he was so upset to see women in lipstick on the podium getting medals alongside “real” athletes.

So, after the 84 Olympics, there was a bit of a backlash, and it was a lot of work to get the team event in there. I do think that event really helped people see the difficulty, with all the lifts and throws, from that very first time in 1996.

Nowadays, I feel that this perception of the sport has evolved and is just changing naturally, because it is so clearly difficult. I mean, anyone who’s ever been in the water can’t watch it at the Olympics and not be like, “Wow, that’s pretty hard.” The underwater cameras, commentators, and improved media coverage have also helped audiences realize what it takes.

IS: Can you tell us what went down for synchronized swimming to be included in the Olympic Games?

VV: There were decades of lobbying and efforts to get in before it actually did. It was an exhibition sport for many Olympiads, starting at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. Then it grew internationally in the 1950s and 1960s, thanks to all these teaching clinics and goodwill tours led primarily by the U.S. and Canada. International competitions started happening in those decades as well, and by the 1970s, the first World Aquatic Championships were held.

The head of FINA [now World Aquatics] at the time was very supportive because his wife had been a synchronized swimmer. So, he was adamant that it was going to be included in the first World Championships for Aquatics. However, the Soviet Union was completely against it because they didn’t have a program yet, and it was too much of an American sport. But he wouldn’t budge, and said it was going in.

These first World Championships in 1973 were a big turning point because it was the first time synchronized swimming was seen as a “World Championship sport” rather than just an exhibition sport. Then, by the next ones, there was a huge international participation, which is part of the requirements to become an Olympic sport.

The Soviet Union really wanted rhythmic gymnastics in the Olympics, while the U.S really wanted synchronized swimming. So, that actually helped in a way. The head of FINA later wrote that he didn’t think synchronized swimming would have gotten into the Olympics had it not been for rhythmic gymnastics. As I talk about in the last chapter, both sports have quite a similar journey and had so many similarities, so it was difficult to justify letting one in and not the other.

Finally, the International Olympic Committee was also really trying to get more women athletes into the Games. Both of those sports were a great way to achieve that, because they were all women’s sports at the time. So all of those factors combined were a big part of the sport being included into the Olympics.

IS: It’s fascinating to see how the fate of the sport is so interwoven with so many other factors — another artistic sport, the need for more women sports at the Games, and this peculiar Cold War setting.

VV: You know, it was largely the Soviet bloc countries that kept it from getting voted in for the 1980 Olympics, which ended up with back-and-forth boycotts between the U.S and the Soviet Union anyways.

But eventually, the Soviet Union came around, again thanks to the dynamics between synchronized swimming and rhythmic gymnastics. The Soviet Union was like, okay, well, you’ve got that, but we’ve got our own women’s sport that we’re going to dominate in. And you have your own sport that you’re going to win in, so everyone’s happy.

I also remember this anecdote from Dawn Bean [author of “Synchronized Swimming: An American History“]. She wrote that a coach from the Soviet Union had come to watch a competition. So she asked her when they would send a team. The Soviet coach responded, “When we can beat you.”

IS: What do you hope people take away from reading “Swimming Pretty”?

VV: I want people to realize that this isn’t just some niche sport. That it’s been really integrated and interwoven with not just the history of women’s swimming, but the history of women’s sports in general, physical education, and even lifesaving. And how it really provided an outlet for women to get into the world of sports. There are all these bigger, important topics around it.

And also, just the difficulty of it too, even though I don’t get into contemporary sport till the end. I wanted synchronized swimming to be seen as a serious contribution to women’s sports and the history of many different entertainment genres as well. It was more influential than it would seemingly be on the surface.

ARTICLE BY CHRISTINA MARMET

Cover photo: Jason Andrew. All other images are courtesy of Vicki Valosik.

If you’ve enjoyed our coverage, please consider donating to Inside Synchro! Any amount helps us run the site and travel costs to cover meets during the season.