When Andrea Fuentes first received an offer from USA Synchro in the summer of 2018, she wanted to laugh. The federation asked her to become the head coach of the senior national team, with the goal of qualifying the team to the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo. The magnitude of what was being asked left her speechless.

“My first reaction was just, ‘Hm, what?!’” she said, laughing. “How do you want to qualify to the Olympics with a super young team that is right now 12th in the world, and with me arriving in November?”

The rules to qualify to the Olympics have recently changed, with 10 teams now able to qualify instead of eight. However, with the mandatory continental quota guaranteeing a spot for one team in Africa and Oceania, this means that the U.S. still must rank in the top eight if it wants to be in Tokyo.

In artistic swimming, it usually takes years to even move up one spot in the world hierarchy. Fuentes only has a year and a half to move her team up by four. And on top of that, she has never even been a head coach before.

The U.S. used to be a premiere nation in synchronized swimming, dominating the world and Olympic podiums especially in the 1980s and 1990s, but eventually had trouble keeping up and started dropping in the rankings in the early 2000s.

Since its last qualification to the games as a team in 2008, USA Synchro has gone through six different coaching staff and a national team roster changing virtually every year, making it near impossible to prepare for the long-term.

What could Fuentes, a four-time Olympic medalist for Spain, do differently to succeed where her predecessors could not? How could she handle the task of qualifying her team to 2020 in less than two years? With the current sense of urgency and simply realizing the system was not working until now, she decided to go for broke and change everything.

She loves a good challenge, and after thinking about it for a few days, decided to embrace it, brainstorm strategies, and do everything in her power to reach that goal. She is ready to give the U.S. team a new life and revolutionize everything, from the routines themselves to the culture of the team and the perception of the nation in the world.

“I know a lot of people on the international stage think that the U.S. will not have enough time to qualify,” she said. “We are not thinking that. I know it sounds crazy. But my story, my career, has taught me that the craziest things are the most powerful, and if you believe in them, they happen. So I’m believing in it, and it will happen (laughs)!”

With a fairly unknown and inexperienced team barely averaging 18 years old, Fuentes is very well aware it is not going to be a walk in the park, especially in a sport renowned for being slow to not only change but mostly to accept that change.

However, she is determined to use her experiences in Spain as fuel to lead her new team. She has indeed lived through history-making as an athlete, working with some of the most visionary and daring coaches of our sport. She knows what it takes, and is convinced she can surprise and bring the U.S. back in the spotlight.

Andrea Fuentes did not even know the sport existed when it was shown to her in her elementary school in Barcelona in the early 1990s. At the time, Anna Tarrés, who would end up becoming Spain’s head coach and bringing the team to new heights on the international stage, was going around local schools in the area to recruit athletes for her club of C.N. Kallipolis.

After watching the video Tarrés showed to her class, Fuentes was immediately wowed. She, her sister Tina, and her best friend at the time immediately signed up to try it out. Fuentes started at the age of nine, with only two to three hours a week after school, but synchro quickly became more prominent in her life. After increasing her training hours every year, she finally entered the Joaquim Blume Technification Center in Barcelona at the age of 13.

The Joaquim Blume residence is a centre regrouping multiple sports, where young athletes can continue their elite training while combining their sporting life with an academic education. It is still to this day where most of the up-and-coming junior synchro athletes train at and prepare to potentially join the senior national team later on at the Centre d’Alt Rendiment (CAR) Sant Cugat.

The structured environment allowed her to successfully compete in the 13-15 and junior national teams where she was coached by Bet Fernández, her club coach who would end up with her throughout her whole career. Tarrés, who had recently become the head coach of the senior national team, eventually requested for Fuentes to be moved up to the senior team at the CAR in order to help the nation qualify as a team for the first time ever at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney. She was 16 years old.

Unfortunately, the Spanish national team missed qualifying by one spot, and to this day Fuentes thinks this was one of the hardest and most defining moments in her young career. She was upset at the result as she realized that training hard did not necessarily equal success and fulfilled expectations. She wanted to quit. Tarrés refused to let her go.

“Anna has a very strong ability to make you dream,” Fuentes said. “She uses that when she knows you need it. She convinced me by just saying she believed I could do great things. Even if at that moment, I was thinking we were not good enough because we were not qualified even after working so hard. But in private, she convinced me by saying that she knew at that moment we were not ready, but that we will be making history in the future. I trusted her, and she was right.”

So, Fuentes stayed. In hindsight, she realized it was simply not their moment. Synchronized swimming was not a popular sport at the time in Spain, and nobody really knew anything about it. Things really took off after the 2003 FINA World Championships in Barcelona, where Spain won its first medals ever. Gemma Mengual won bronze in solo and in duet with Paola Tirados, and the nation tied for silver in the free combination event. Mengual quickly grew to celebrity status and brought much-needed attention to synchro in the country, which eventually became “the sport of Gemma Mengual.”

Finally winning medals was not the only thing that helped the growth of synchro in Spain. Indeed, the country started being engrossed in the team also thanks to Tarrés’ personality, and knack for marketing and getting the media’s attention.

“We were this little group of crazy and strong women,” Fuentes said. “And Anna, she’s very good with the media and she was so interesting for them, always coming up with crazy things. She wasn’t just saying, ‘Yes, we started training for the season.’ No, she would tell them we were creating swims with lights, collaborating with this person, or that she was just inventing crazy things. The media was interested in us, and I think this was the key.”

Fuentes was never one of those athletes whose dream had always been to go the Olympics. She contemplated it, and remembered watching replays of the 1996 Olympics on repeat, but it never really became a specific ambition for her. As an athlete, she liked to take it one day at a time, be in the present moment, and do her best every day, believing that everything would work out.

When Tarrés took over in 1997, the team ranked towards the middle of the world rankings, hovering around the 10th to 12th place, and the powerhouses then were Russia, Canada, the U.S and Japan. However after 2003, the possibilities of an Olympic dream and an Olympic podium were becoming more and more realistic. At the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens, the Spanish team not only qualified but finished fourth, only 0.667 points behind the U.S.

Using this as fuel, the team doubled down in training and went on to win four medals (one silver and three bronze) at the 2005 world championships. At the 2007 world championships, Spain finished with six medals (four silver and two bronze). The country was now a clear favorite for the podium at the 2008 Olympics.

“We never thought that in less than 10 years, we would get an Olympic medal,” Fuentes said. “I think even [Tarrés] did not believe this was happening. We were working as much as we could, improving every day and finding our limit. The first step was, we wanted to get to the Olympics. And suddenly four years later, we were in the fourth place in the Olympics, then four years later an Olympic medal! But we never really thought about it every day.”

In 2008 in Beijing, Spain won silver in team and in duet, where Fuentes was swimming with Mengual. The world and European medals kept coming for the Spanish team, and four years later at the 2012 Olympic Games, Fuentes won another silver in duet, this time with Ona Carbonell, and bronze with the team. Under these 15 years with Tarrés and Fernández, who was also part of the coaching staff of the senior team, the country accumulated four Olympic medals, over 25 world championship medals, and 25 European championship medals.

During that time, Spain was recognized by the entire synchro community as revolutionary and as an innovative, risk-taking team that one could always count on to come up with unique choreography, gravity-defying acrobatics, or original costumes. Some of Spain’s most famous and attention-grabbing routines came during that time, with amongst others Dali, the Circus, the Haunted House, Queen, Stairway to Heaven, the Sea or Cats.

The creative process for these routines was ultimately a significant team effort. Tarrés would put the music on, and let her athletes improvise and come up with ideas. Then, they would try to gather all the pieces of the puzzle together to create a world-class choreography. Fuentes believes this process made each of the swimmers more independent and not afraid to come to practice with suggestions, however crazy they may seem.

Some of the swimmers’ propositions would be selected, some not, but all of them would ultimately be welcomed to contribute: “She was always thinking that if the coach thinks only by herself, it’s only one brain, but if we all think about something, we are 13 brains. I try to be the same as a coach in this sense.”

The swimmers were not only greatly involved with the choreography process, but Tarrés would also not hesitate to ask for external help in other areas she knew she was not as good in, a process that could ultimately benefit everybody. Fuentes remembered working on technique with Japan’s legendary head coach Masayo Imura or 1996 French Olympian Anne Capron, and on landrilling with former Great Britain Performance Director Biz Price. Gana Maximova, currently the coach of Russia’s mixed duet, also came in and taught them how to properly improvise, to be freer in the water and to show their personalities.

One of Fuentes’ favorite routine is the ‘Africa’ routine, which was created for the 2007-2008 seasons, as it represents in her eyes when the team truly had a breakthrough. To start off, the choreography changed the way team routines were constructed as for the first time the first lap was only made of highlights and transitions, with no big hybrid until the end of it.

“Everybody was telling us this would not work,” she said. “We were taking the risk to do it, and we were changing the status quo. Now it looks normal, but in that period we were actually afraid to show what we do. But Anna said, ‘Let’s do it, we don’t listen to anybody and we do it.’ It was the only time we beat Russia in artistic. We were very proud to show it in the end.”

That routine was also memorable as it introduced what has now become an iconic feature of Spain’s team: the bridge lift. It originally was Fuentes’ idea, but most of her teammates and coaches dismissed the crazy thought at first and told her to forget about it. Fuentes only asked for 10 extra minutes after the end of training each day for the team to work on it, without the help of the coaches. Her teammates caved in and took it upon themselves to give it a try. It took six months, but they eventually presented it to the coaches, who were astonished and proud that they had made it work.

In 2012, this bridge lift eventually evolved, this time through Tarrés’ vision of having somebody jump above it. Once again, the swimmers thought it would be impossible to do, and almost questioned the sanity of their coach. Tarrés believed they could make it. They started out with 12 people, and eventually made it work with eight, the required number of athletes in a team routine at the Olympics. This second version of the bridge was also a success.

Fuentes recognized that working with Tarrés as an athlete was very hard, that she felt a daily pressure to never relax and to always push herself to be at her best, but that it also shaped her into the woman that she has become.

“Before [Tarrés] arrives at the pool, you can tell she’s there,” she said with a laugh. “This is an effect she creates with everybody. She has this big presence, and she is not afraid of anything. She’s in that limit between genius crazy and very brave. She doesn’t care about anything, even if sometimes it’s too much. But that’s what it is, breaking boundaries. Not everybody is brave enough to do these things. When you have somebody like this as a leader, you become a little bit like this too. You get inspired with this fearless sensation.”

After Beijing, there was a significant generational change for the Spanish team, and only three of the 2008 Olympians ended up continuing all the way to the 2012 Olympics. For Fuentes, the two teams could not be more different. In her opinion, the 2008 team was very symbolic as most of them had started on this journey together since the missed qualification in 2000, and were the catalysts of the evolution of Spanish synchro.

“It was not always super easy as a team [in 2008],” she said. “That team had a lot of different and strong egos and personalities. We had sometimes a lot of problems, but we were super professional in a sense. Like, we don’t need to be friends, all of us, but we are all fighting together for this dream. It was eight years of evolution together, and we knew a lot of persons on the team would quit after, so this experience was very beautiful.”

To prepare for the next quadrennium, the renewed roster was filled with many young athletes who had just known success in the junior category. The goals then were to not drop down the rankings, to continue fighting for medals, and to keep the innovation that was expected from the nation. Fuentes, who had become one of the veterans of the team, recalled how united and fun the team was heading into 2012, as each athlete was focused on enjoying the process while also working hard to make it no matter what.

She did not only get the chance to grow as part of the team, but she was also moved up to the duet ahead of the 2008 season with Gemma Mengual, a position she never expected to find herself in.

“I was a nobody and she was my idol,” Fuentes said, laughing. “I just copied exactly what she did. I had the master here and I just wanted to get closer to her level. I was watching everything she was doing, just following and learning.”

With a shared motivation to reach the Olympic podium in duet, the two pushed each other. Fuentes knew her skills were not up to Mengual’s yet but she was eager to improve, and constantly asked her partner for advice on technique. Meanwhile, Mengual herself was challenged and motivated to not rest on her laurels with this youngster coming up fast on her heels.

The 2008 Olympics in Beijing were extremely nerve-racking for Fuentes. It was essentially the first time she was competing in the duet at a major world event as she wasn’t part of it yet at the 2007 world championships: “I just remember a super, super high pressure inside. I felt I was falling over because of the nerves on deck. I remember thinking I would fall in if I didn’t get in already. I never saw so many people looking at us.”

The two comfortably won the silver medal and finished slightly less than a point behind the Russians. Mengual retired (for the first time) after the 2009 FINA World Championships, which resulted in Fuentes now being paired up with Ona Carbonell. Carbonell, 19 at the time and poised to become Spain’s next big thing, had already competed at the 2007 world championships with the senior team but had not made the cut for the 2008 Olympic team.

“I had found somebody who was as crazy as me,” Fuentes said of Carbonell, laughing. “I had never found somebody who wants to train as much as me, who wants to work even more after training! It was like finding our other half.”

Carbonell felt the same, and the two instantly bonded. They became relentless in their training, challenging themselves and pushing each other to strive for excellence. They always wanted to go the extra mile, asking to work even longer after practice had ended or meeting together outside of official training time to landdrill their routines on their own.

At the 2011 FINA World Championships in Shanghai, they won bronze in both technical and free duets, but were determined to win the silver medal the following year at the Olympics ahead of China.

“We had a deal with Ona,” Fuentes said. “Whatever [the coaches] say, even on the craziest day, we will ask for one more run-through. And since we are volunteering, we will do it even better. We will not complain about how hard the training is, we will ask for even more. So every day when the time arrived, even if we could not move our legs anymore, we would still ask, ‘Anna, one more.’ It was hard but the strength we had inside…I think it was the key of our success. We were just in love with improvement.”

Following the qualification round during the 2012 Olympics, Fuentes and Carbonell were trailing the Chinese pair by 0.22 points. After a heartfelt and raw free duet performance in the final, they were able to snatch the silver medal by the slimmest margin of 0.03 points.

Fuentes also got to perform in the solo event for Spain, although it was not necessarily something she had wished for. Mengual had been the country’s soloist for decades and after her retirement in 2009, that task befell on Fuentes.

She did not want to do it, did not want to train solo for the national team, and did not feel confident in performing in that event on the international stage, especially coming after Mengual’s legacy and with a completely different style of swimming. Initially, the process did not go as smoothly as her and her coaches had hoped.

“It was difficult for Anna because with Gemma, you put the music and she improvises,” Fuentes said. “With me, it was challenging. She was trying to have me be like Gemma, and I did not feel like Gemma. It was not like me at all.”

Fuentes had previously performed her own solos on the national stage for her club of C.N. Kallipolis, where she could let her free-spirited, unconventional side out. She had always wanted to break the status quo in that event, change the notions of what a soloist should look like, and find a meaning and a purpose with her choreographies.

She needed to feel connected to the music, and loved bands that could be considered eccentric choices for synchro, like Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Neil Young or Neutral Milk Hotel. She fondly recalled one of her most memorable performance at Spanish nationals shortly after the 2004 Olympics when she was in her early 20s, where she showed up boasting a punk hairstyle to swim to ‘Dark Side of the Moon’ by Pink Floyd.

“I was very rebel at that time and bored about the same stuff in synchro,” she said. “I remember how people were looking at me after and running to congratulate me. It’s one of my best memories because I created something that was pure and that did not involve other’s opinions.”

Another one of her remarkable solos came a few years later, and revolved around the liberation of the woman. She started the routine covered by a black fabric with a very dark music, and finished it by untying her bun and letting her hair completely loose, to the screams of Janis Joplin.

“I wanted the maximum freedom of expression,” she said. “I remember some judges putting a 10 in artistic and others a five. It was so shocking, but I was proud to do it. Some judges were upset because I was using objects, and maybe too much freedom, but it was my intention to provoke feelings. I remember a man coming to me after this solo, crying, to thank me. It was the best gift for me.”

However, those ideas would likely have not been received well on the international stage. Still struggling to create a routine for Fuentes, Tarrés eventually called up on Maximova and three-time world solo champion Virginie Dedieu to come on over to help Fuentes create a routine that would still fit within the rules and unspoken expectations, while remaining true to herself.

Fuentes and her coaches invested time in finding her own style. She still enjoyed the process, and in the end could bring a little bit of her own spunk, although subdued, to the international scene with routines to Janis Joplin’s ‘Summertime’ and Edith Piaf’s ‘Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien.’ She went on to win silver in free solo and bronze in technical solo at the 2011 world championships.

“I always felt like I could do more in solo,” she said with a smile. “But I was already 27 when I started my first solo, so it wasn’t my goal. If I had done one more year for Barcelona after the Olympics, I would have really done my style and not care about anything, and be more fearless about showing different stuff. Even now, I feel I could do some things on the international stage to change the way… but it’s okay!”

She had originally intended to retire after the 2013 FINA World Championships in Barcelona set in the summer so she could finish her career at home. But in September 2012, the president of the Spanish federation Fernando Carpena announced that he would not be renewing Tarrés’ contract due to “professional reasons and sports policy.”

The transition to a new coaching staff turned out to be difficult for Fuentes, which coupled to nagging injuries, issues in her personal life, and simply the fatigue of nearly 15 years at the elite level, took away her motivation and willingness to continue. She tried and hung around for three months, but eventually started to skip training sessions.

“After the second time I realized this was not me at all,” she said. “I realized I didn’t want to be there anymore. It was time for a change, time to accept it.”

Fuentes called it quits in January 2013. She ended up retiring as Spain’s most decorated swimmer, with four Olympic medals and nearly 30 world and European medals. With her Olympic medals, she is also still to this day the most decorated Spanish female Olympian of all time, tied with Mireia Belmonte (swimming) and Arantxa Sánchez Vicario (tennis). Never did she think as a small nine-year-old that she would ever reach such accolades in her athletic career by the time she turned 30, and against all odds.

“Before Sydney 2000, a sports psychologist told Anna that she should tell me to go home because I would never get anywhere,” Fuentes said. “I’m lucky because Anna didn’t listen to him (laughs)! A lot of people were saying I would not succeed, but this is the proof that nobody has to be the same. I was not listening, just doing my job with passion. When you work well and with passion, you don’t have to think about the goal, something good will happen for sure.”

Fuentes enjoyed her first few years of retirement away from synchro and looked forward to finding her own path outside of just being an athlete. She started a family and had two children with her husband Víctor Cano. The two created Synkrolovers, an online platform that shares technique, nutritional or mental tips and that also sells synchro merchandise. She tried herself at an aquatic show company ‘Olympias Events‘ with some of her fellow former teammates. She begun coaching in international summer camps, and was a consultant for a few countries at the elite level like Great Britain, Australia, Switzerland or San Marino amongst others, to help them with their choreographies, mental skills or physical conditioning.

“I was enjoying it because it was beautiful to show how to enjoy the process of improving,” she said. “I think one of my strengths is to show not only how to work, but to learn to trust yourself and how to feel stronger as a person if the sport helps you to achieve goals.”

Then, the e-mail from USA Synchro came. The American federation had been looking for a new head coach in the middle of its rebuilding and wanted to qualify a team to 2020. It had been a tumultuous few years for the U.S team, with a handful of leadership and coaching changes alongside struggles to stay in the top 12 at the world level. The U.S. had not qualified to the Olympics as a team since 2008, where it finished fifth, although it was present in 2012 and 2016 with a duet.

The federation wanted to bet on her. She loved the idea of bringing a former synchro powerhouse back to its glory days. She had lived through history-making in Spain with innovative and unique choreography, and she knew what it took to climb up the world rankings all the way to the medal stands. So, she and her entire family moved across the world to California, near San Francisco.

“I have a strong determination to accept difficult challenges and make them happen”, she said. “It’s one of my passions. The harder it is, the more it attracts me. I feel this is my place in this moment of my life. And I feel like my character is more connected to the U.S. culture than other countries, in terms of innovation, action and this deep willingness to be at the top.”

After spending nearly 20 years with Tarrés and Fernández, Fuentes knows it has not only influenced her coaching style but has also given her the motivation to break boundaries and push the envelope of the sport in her own way. She hired Reem Abdalazem as her assistant coach, who is just as ready to take on this massive challenge with her.

“I knew I wanted somebody very powerful with me,” she said. “If you want to be the best one, you have to be involved with the best ones. I learned this from Anna when she chose Bet Fernández who for me is a very powerful coach. They were super connected, and both of them trusted each other in everything. I have the same feeling with Reem.”

Not only is this Fuentes’ first time as a head coach of any team, but the challenge is even bigger as the two are leading a young team made of all but one athletes who still technically qualify for the junior category. Anita Alvarez, a 2016 Olympian in the duet, is the only veteran.

Nonetheless, this underdog yet scrappy team is filled with strong characters who are all in, ready to tackle this challenge and to embrace the changes in order to represent the U.S proudly on the international stage. Both Fuentes and Abdalazem know time is too short to truly make a significant difference in the swimmers’ technique, so they are betting on artistry and strengthening the mental preparation of their athletes first.

“I think everything we are changing is coming from my story in Spain a little bit,” Fuentes said. “We want them to feel the routine, to own the routine, and this is very powerful to me. We are changing a lot of the expressions, we are doing everything very deep, and our goal is to create goosebumps in all the people. We are teaching them how to live the choreography and perform to create feelings and a connection with the judges and the audience. Because this is why we do synchro, right?!”

The focus obviously must be on the Olympic events, which are the duet and team events. The first step was to create a brand new choreography for the free team which will be to the theme of ‘Robots.’ They will perform a new lift that has never been seen before. Fuentes had known for years she wanted to create a routine to this theme, and she believed it was the perfect moment as this style is very popular in South Korea, where the 2019 FINA World Championships are held in July, and in Japan where of course the 2020 Olympic Games will occur. The technical team will also change and will be geared more towards a warrior theme.

The duet routines are also revamped, with a new free choreography to R&B music which is something completely different and unusual in the world of synchro, where the conventions usually revolve around classical music, Cirque du Soleil, or famous movie soundtracks. The duet composition is still a bit up in the air, with Alvarez, Ruby Remati and Lindi Schroeder all working on it and gunning for a spot.

“The tech [routines], we are looking more for the execution and the elements,” Fuentes said. “For the free duet and free team, we are looking to change the status quo.”

On the mental side, Fuentes and Abdalazem are aiming to empower their athletes and to change their own perceptions of themselves. They want them to understand that they are powerful, that they are mature enough to be on the senior team, that they belong there and can fight for their Olympic dream like anybody else. They want them to love and trust the process, to enjoy the sport, and to realize one of the key factors in achieving their potential is to believe in themselves.

Abdalazem, a two-time Olympian for Egypt, was more familiar with the U.S. system than Fuentes. She swam for Lindenwood University and became a collegiate and U.S. National Champion before moving on to coaching age groups in the club of ANA Synchro, where she was also highly involved in the athletes’ development in and out of the pool.

“[Reem] knows how to get to their minds and to make them trust themselves,” Fuentes said. “This is the first step, to make them believe in themselves no matter what. Then, I can grab these minds and make them perform at their best potential with the best choreography. Sometimes I forget they are young, because I see that they are growing so fast in their maturity. It’s so beautiful and rewarding to see.”

It’s barely been seven months, but Fuentes can already tell it’s a completely different team. The U.S. will show off its new routines for the first time this weekend at the Synchro America Open in Greensboro, N.C. Then, the entire squad will fly to Barcelona for the Spanish Open the week after, before finally competing at the FINA World Championships in Gwangju, South Korea, in July.

“I’m very excited to show the world what we have done,” Fuentes said. “I hope that the world will appreciate. We are more passionate than I’ve ever felt in my life, so I think it will be good. It’s important that people are ready to see our changes.”

Article by Christina Marmet.

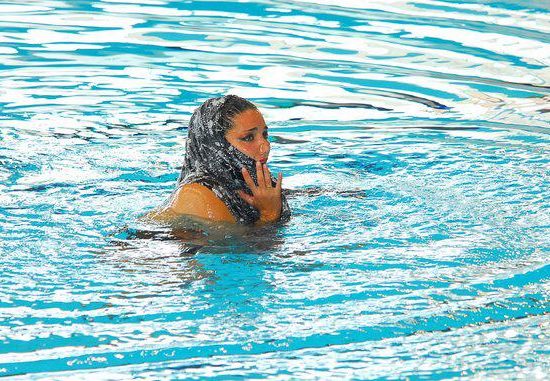

Cover photo by Liz Corman.