When she was little, Kseniya Sydorenko collected the scoring papers of each judges during local competitions. She used this opportunity to intensely watch each routine. Back at home, she told her mom she wanted to win a medal: “Only one. It doesn’t matter which one, but a small medal and I would be happy.”

While representing Ukraine internationally for nearly 12 years, her drive and dedication to reaching her childhood’s dream have been indisputable: 14 European medals, including two gold, and two World Championships medals adorn her room at home.

Beyond the medals, she also competed at three Olympic Games, and contributed to the rise of the nation, from barely making it into a world final all the way up to the medal stand. But her career has sometimes felt like a rollercoaster, going from highs to lows, from standing on European podiums to missing an Olympic qualification or medal within a few months.

Born in Kharkiv in northeast Ukrainian SSR in 1986, Sydorenko first started in artistic gymnastics at the age of four. After a few years and upon realizing she was maybe too tall for this sport — she grew to be 1.80 meters tall —, her parents took her to the pool to learn how to swim and stay in shape.

Synchronized swimming was essentially unknown in the newly independent nation at the time. The Soviet Union’s team had competed one last time in 1991 before the dissolution of the state that fall. In 1992, the former Soviet athletes swam at the Barcelona Olympic Games under the Unified Team banner. Ukraine finally made its first international appearance at the 1993 European Championships.

One year later and removed from the worries of geopolitics, an eight-year-old Sydorenko discovered synchro through her ballet teachers, who believed her spindly figure would make her a perfect fit for the sport.

“Really, I never was super talented,” she said. “It all came later. I had strong muscles because of gymnastics, but everything was all so difficult for me… All the splits and bridges, everything was very hard. I had to work very hard on that.”

Her parents’ intentions for a low-pressure, after-school activity for their daughter were rapidly forgotten as she found herself in the midst of national team selections. She eventually competed at the 2002 and 2003 European Junior Championships, and the 2002 and 2004 FINA Junior World Championships. In 2005, she was propelled to the senior national team for her first World Championships in Canada, amongst the cream of the crop of synchronized swimming.

Back then, Ukraine was not nearly as dominant as it is nowadays, and the coveted medals were far-flung. In Montreal, the Ukrainians finished eighth in solo, ninth in free combination, and 10th in duet and team. These championships however remained significant for her as she made her first appearance in the duet event alongside Daria Iushko, who had just placed 11th in duet at the 2004 Olympics.

After 2004, most of the senior national team members decided to move on. Iushko needed a new duet partner, and the national team staff deemed Sydorenko, fresh from the junior team, the perfect match.

Photo: G.Scala/Deepbluemedia.eu/Insidefoto

“[The duet] was big stress,” she said. “I said at the beginning I didn’t want to do it (laughs). Daria was already an athlete with a big experience, and I was just from the junior team. But in the end, we competed 10 years together, with the duet and team. We are very close, we know everything about each other. We are still best friends.”

Ukraine continued its slow progression up the European and world rankings, one position at a time. At the 2007 World Championships, Sydorenko and Iushko placed eighth in technical and free duet, while the rest of the team placed sixth in free combination, eighth in technical team and ninth in free team.

While the full team was still far from qualifying to the 2008 Olympic Games, the Ukrainians finally won their first European medals. That year in Eindhoven in the Netherlands, Sydorenko and her teammates won three bronze in the duet, team and free combination events (the technical and free events were then still combined for the final rankings in European Championships).

A few months later, Sydorenko arrived at her first Olympic Games in Beijing with Iushko, where they finished eighth. She was well aware an Olympic medal was unattainable then, but she had now experienced what it felt like to stand on the podium. She knew she wasn’t going to stop there.

“[Daria and I] already were swimming three years together, almost four,” she said of her first Olympic experience. “Of course Beijing was exciting because it was my first time, and China had a really great organization. I remember the stands in the pool were full. But we were just the duet. Without the team, it’s always a little bit harder because you always feel stronger all together.”

Riding its newfound momentum, the Ukrainian team also wanted to reach new heights and aimed to qualify to the 2012 Olympics for the first time. The European medals kept coming in 2010 and 2012, while the country continued inching along the world rankings. At the 2011 World Championships, Ukraine finished sixth in technical team, free team, technical duet and free duet. Most importantly, the nation was within less than half a point of Japan, and an Olympic berth as a team was certainly within reach.

Less than a year later at the 2012 Qualification Tournament, only the top three teams would be able to qualify to the London Games. After the technical team event, the Ukrainians tie the Japanese team for third. But two days later in the free team event, Japan edged out Ukraine for the last spot by 0.23 points. While Sydorenko and Iushko qualified easily as a duet to their second and third Olympics, respectively, they did find themselves dealing with mixed emotions and the devastation of their teammates.

“It was really, really hard,” she said. “For us with Daria it was a bit easier than for the other girls because we were still going there. But it was a really sad situation, really. It was so, so little…0.2 points. Nothing.”

Sydorenko and Iushko ultimately finished sixth in London, satisfied with their performance and the positive feedback from their coaches Svetlana Saidova and Olesia Zaitseva, which mattered to them more than the actual score or placement. Nonetheless, they both decided to retire after these Games.

In the meantime, the rest of the team trudged on. Fueled by the disappointment of 2012 and the possibilities of a new quadrennium, the Ukrainians finally won their first world medals in 2013: three bronze in technical team, free team and free combination. Sydorenko watched it all unfold and realized she couldn’t stay away from the pool.

“I just felt that I wasn’t finished,” she said. “I rested, and understood that I could do more. I missed competing, the process of practicing, the feeling of standing on the podium, or hearing the applause after the routine… You can’t replace that with anything.”

Photo: P. Mesiano/Deepbluemedia/Insidefoto

Sydorenko returned to the water and geared up for the 2014 European Championships. The new duet had already been decided, but she was happy to now solely focus on the team routines. That year in Berlin, the Ukrainians became European champions for the first time in history in free combination, and moved ahead of the perennial powerhouse Spain in the rankings.

“This competition was just, ‘Wow,’ for us,” she said, smiling. “We didn’t expect it, so it was really a big surprise. We work a lot, but every time it’s a big surprise when we go up. In synchro, people say every time it’s impossible, that everyone has their level and you never will grow. But everything is possible, really. I see that it is. Of course, everyone wants to go up fast, but maybe you just need a little bit more time than you want.”

As fate would have it, a world medal eluded her again in 2015 as Ukraine finished fourth in technical team, free team, and free combination behind Japan, who had by then become its main rivals. Daria Iushko had also returned that season, on her own quest for a world medal and an Olympic berth with the full squad.

A few months later at the 2016 Olympic Games Qualification Tournament, the tables turned for Ukraine. This time, it finished in first place and ahead of Japan by the slimmest margin of 0.0525 points. Ultimately, both qualified full teams to Rio, but this was truly a remarkable moment for the up-and-coming country. Sydorenko was now on her way to her third Olympics, and with her entire team for the first time in the nation’s history.

Now closer to an Olympic medal than ever before, the Ukrainians doubled down on training, with only a few months left before the start of the competition in Rio. Not wanting to leave anything behind, they called on Anna Tarrès, former head coach of Spain and renowned choreographer, to come create a new free team routine.

“It was a really interesting routine,” Sydorenko said. “But it was super difficult. Really after one [run- through], we couldn’t feel anything anymore (laughs). The first part was one minute with a lot of lifts, and I was almost all the time under the water. So after one minute, I just wanted to finish the routine and get out!”

They kept their intricate and surprising “Illusion” choreography under wraps until the very last minute. They only showed it off for the first time at the Olympics, topped with original swimsuits that got darker in the water. Unfortunately, it wouldn’t be enough to fend off Japan this time. Ukraine finished fourth again, missing the long-coveted Olympic medal by 0.5976 points.

“Everyone was super, super sad,” she said. “It was so little again. And almost all the team was finished. I was thinking for a few months if I would continue or not. But there were the World Championships, and I thought, ‘Maybe I need this.’”

While Iushko called it off for good, Sydorenko decided to push through to Budapest. She still had not won a world medal, and she wanted to put the bitterness of Rio behind her. This time, she had to deal with a completely new team, and found herself swimming alongside athletes sometimes more than 10 years younger than her. However, she enjoyed the energy she felt all around, and her teammates’ eagerness to improve and continue making history for their country.

There is no secret recipe to Ukraine’s success and rise, except maybe a lot of hard work, self-awareness and patience. Season after season, the nation competes in as many meets as possible, and in mostly every single event. The coaches, Saidova, Zaitseva and Valeria Mezhenina create new routines at an impressive pace, unveiling groundbreaking acrobatics or innovative hybrids. Since the inception of the FINA World Series in 2017, Ukraine has won the most medals out of every nation every year, and has established itself as one of the new powerhouses.

“It is not always easy of course,” Sydorenko said. “It’s just hard work. Our coaches always want to improve, so we often change our programs. With that, they try to improve, improve, improve, and try something new. And of course, it’s only working hard. I don’t know anything different.”

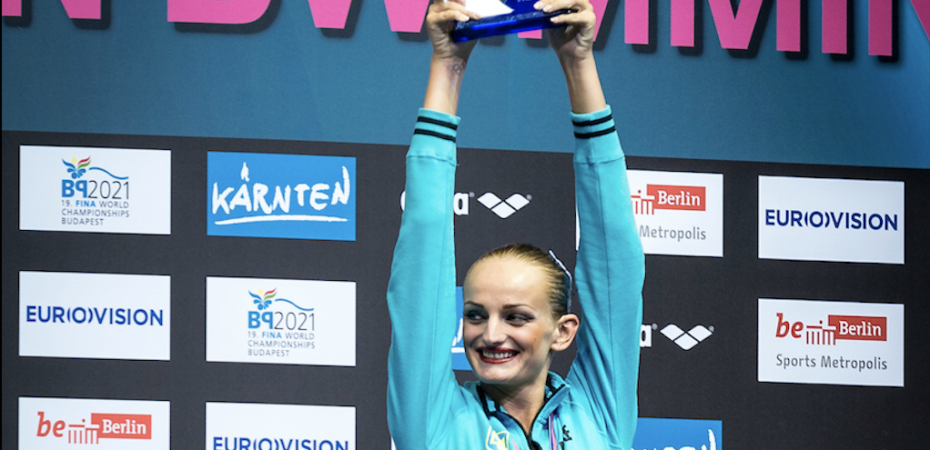

In that summer of 2017 in Budapest, she was finally able to stand on a world podium, for the first time since her senior debuts 12 years prior. The meet didn’t start off so well as Japan edged out Ukraine once again for the bronze in the technical team event. But the Ukrainians roared back for bronze in free team and silver in free combination, both times ahead of their persistent rivals.

Photo: Andrea Staccioli/Deepbluemedia/Insidefoto

“When we became third it was like, ‘Finally! I did it!’” she said. “It has taken a lot of years. I missed 2013 when the girls became third. So finally, I did it! I had already done three Olympic Games, but I didn’t have a world championship medal!”

After Budapest, she competed at the last world series stop in Uzbekistan, and realized she maybe needed a change of scenery. After a few months, she decided to take up the offer to coach the Slovakian duet of Viktoria Reichova and Natalia Pivarciova ahead of the 2018 season.

“I accepted because I wanted to try something by myself,” she said. “All these years, I did all the time what the coaches told me. It’s not a bad thing but I wanted to see if I could do something as a coach.”

Meanwhile, Ukraine continued to rise and become an undeniable dominant force. At the 2019 World Championships, it qualified a team to the 2020 Tokyo Games, won its first-ever world title, and earned an additional five bronze medals. Most importantly, the Ukrainians comfortably finished ahead of Japan in all Olympic events. The Olympic medal is now certainly at their fingertips.

“As a team we continue to improve really fast,” Sydorenko said. “This team, these girls are impressive because holding the results is harder to just grow. It shows to everyone that Ukraine is so strong.”

Artistic swimming is now a bit more recognized in the country thanks to the good results of the last few years. Members of the national team all live and train in Kharkov year-round. While lacking an official, centralized training center, the athletes have all they need with a pool, a gym, and different consultants coming in for acrobatics work or physical therapy, amongst others.

Back in Slovakia, Sydorenko enjoyed her work, discovering a new country and culture, and being able to bring something new and different to her athletes. Reichova and Pivarciova last competed at the 2020 French Open before the COVID-19 pandemic put the sporting world to a halt. Instead of continuing with the selection procedures for the junior and senior competitions of the season (which have now been cancelled or postponed), they all were forced into lockdown.

The 34-year-old returned to Kharkov with some unfinished business. The quiet but persistent voice of the little girl who started this crazy adventure more than 25 years ago is still there, contemplating the possibilities of doing the impossible.

“Everyone told me fourth place is a good result,” she said. “But it’s not an Olympic medal. This medal is still somewhere inside of me.”

Article by Christina Marmet

If you’ve enjoyed our coverage, please consider donating to Inside Synchro! Any amount helps us run the site and travel costs to cover meets during the season.

[…] Sydorenko will make her comeback to the Ukrainian squad team at this competition. Chasing her Olympic medal dreams, she resumed training for the elite level about a year ago. She had begun a coaching career in […]