Artistic swimming would not be the sport it is without the dynamics between athletes and judges. No competition can happen without one or the other. While teams cannot control the judges’ scores, they do highly value their inputs, and always seek feedback to reach higher marks.

This search of performance and optimization goes both ways. Judges too are always aiming to improve, to apply the code of point accurately and justly, and to receive constructive criticism on their own work. Who gives that feedback to them? How can they sharpen their own skills as well?

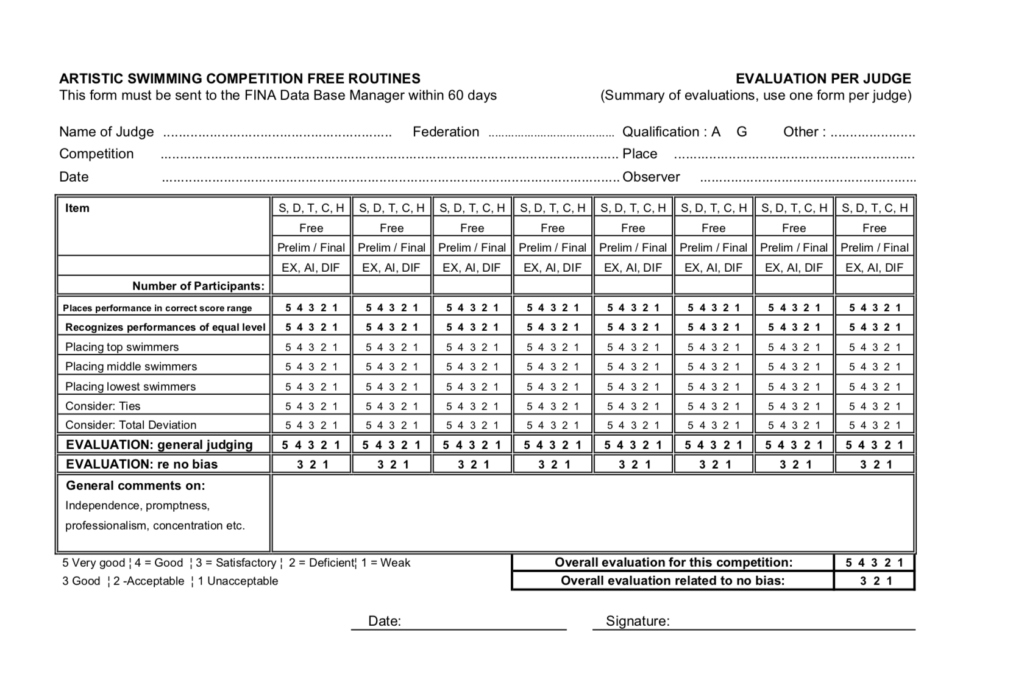

Currently, international judges are overseen by evaluators during competitions. Evaluators will review and rate each judge based on different criteria. They will then fill out and send individual reports within 60 days. In smaller, local competitions, there rarely is any formal evaluation procedure.

For María José Bilbao, Núria Ayala, and Damià Palmer, this was not enough. The three Barcelona-based judges wanted to find a way to obtain a near-immediate assessment of their work during a competition.

Bilbao is one of Spain’s most recognized and respected FINA A judges, a current evaluator, and a member of the FINA Technical Artistic Swimming Committee (TASC). Ayala, a two-time Spanish Olympian, is a fellow A judge and current head of the artistic swimming section in the Catalan federation.

After numerous brainstorming sessions, Palmer, a Catalan judge working on his national certification, figured he could use his background in statistical analysis. He aimed to create a data-oriented evaluation for each judge, deliverable within minutes. Thus in 2016, the Statistical Technique for Artistic Swimming (STATS) project was born.

“We had the feeling that as judges, we leave the chair and we have no idea what we have just done, especially after a long competition,” Palmer said. “It was first about finding a way to express the whole competition, not just the highlights or big mistakes that you usually remember. We wanted to create a short summary, something that will give the full picture and help judges learn. And we wanted to have it right away.”

Indeed, the trio thought judges needed more instantaneous feedback. In national meets, time is of the essence and the head judge often has very little time to give in-depth, personalized feedback. Internationally, many judges naturally don’t remember what they did months after a specific competition.

“One of the worst feelings is when you feel good with your marks but your colleague in the same panel had something completely different,” Bilbao said. “If there is no discussion immediately or facts in your face, you stay on your own personal impression. You keep on thinking that you are right, and the other is wrong. We have been in this system for very long. And after 60 days, you don’t remember anything, so you learn nothing.”

How are judges currently evaluated?

Each international judge is classified as either a “G” or “A” judge, the latter being the highest level. During elite competitions, FINA judges are looked at by sanctioned evaluators, who themselves have been A judges for at least five years. Receiving good evaluations is crucial for judges wishing to move from G to A, or for A judges to maintain their classification.

Evaluators judge the same routines as everyone else, but their scores do not count towards the final score. Ultimately they will, to the best of their judgment, determine how accurately a judge scored routines and figures according to the FINA Handbook. Additional factors for the evaluation are also considered, like proper use of the score range, independence of opinion, evidence of bias, level of concentration, ability to make decisions, or overall professionalism. Evaluators then review and compile their data into reports, which are subsequently sent to the FINA Office and each judge within 60 days.

At the local level, judges usually only have short meetings before and after every event. However more often than not, competitions run on a tight schedule, so they have very little time to compare notes and discuss. Palmer admitted that in his experience, they all would rather spend time talking about the next event than arguing about the last one.

What does STATS do?

“We try to define your opinion and your actions with data,” Palmer said. “This data allows you to have everything fast, to open your mind to what other judges are doing or looking at, and to question your own performance in a productive way.”

Once an event has concluded, Palmer enters all relevant data and scores into his STATS program. He can then deliver full documents and graphs to judges often within the hour. So far, the slowest part has actually been to get all the results to him in a timely fashion.

“We were really looking for a tool that helps judges learn by themselves,” Ayala said. “You can see a lot of things very fast [with STATS]. Like if you always have mistakes in the middle of the competition or for the medium-level swimmers, if you’re three tenths up on the best or weaker swimmers, or if you lose concentration at about the 30th swimmer in figures. These help you do something to improve and have a better reaction to your actions right away.”

“Our work is to try to identify if a mistake is random or systematic,” Palmer continued. “We want to correlate the deviation to see if there is any logic or not. The data helps in seeing and interpreting that clearly. So, we can see if a judge made a mistake because he or she lost concentration briefly, or got a bit tired in the middle if the event is long. Or, we can also see if the mistake is more a logical consequence of a judge’s own thoughts and opinions.”

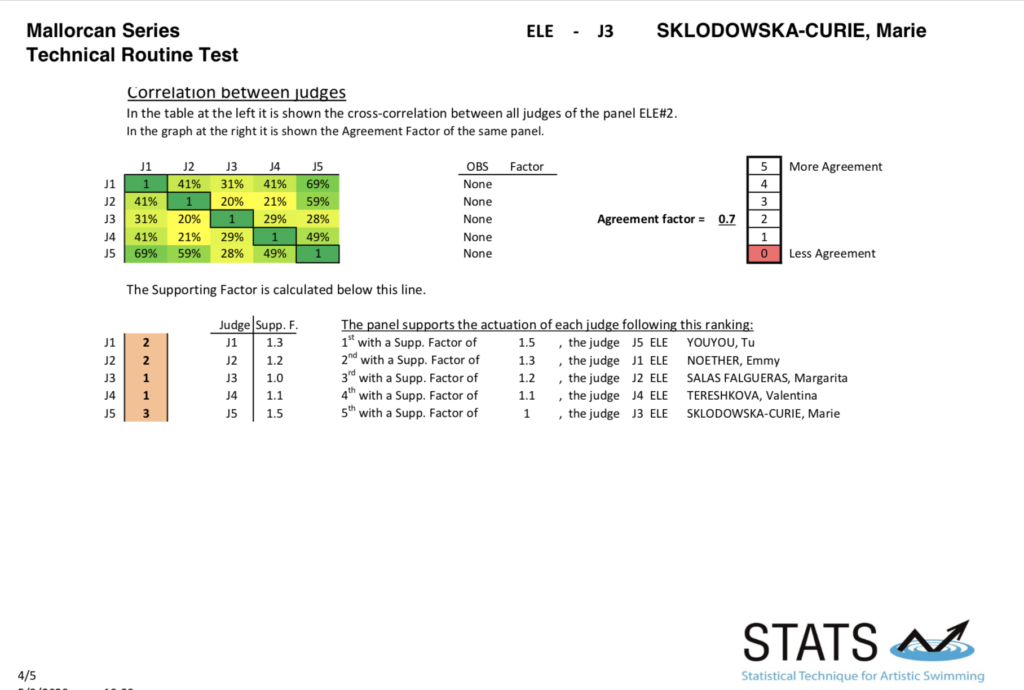

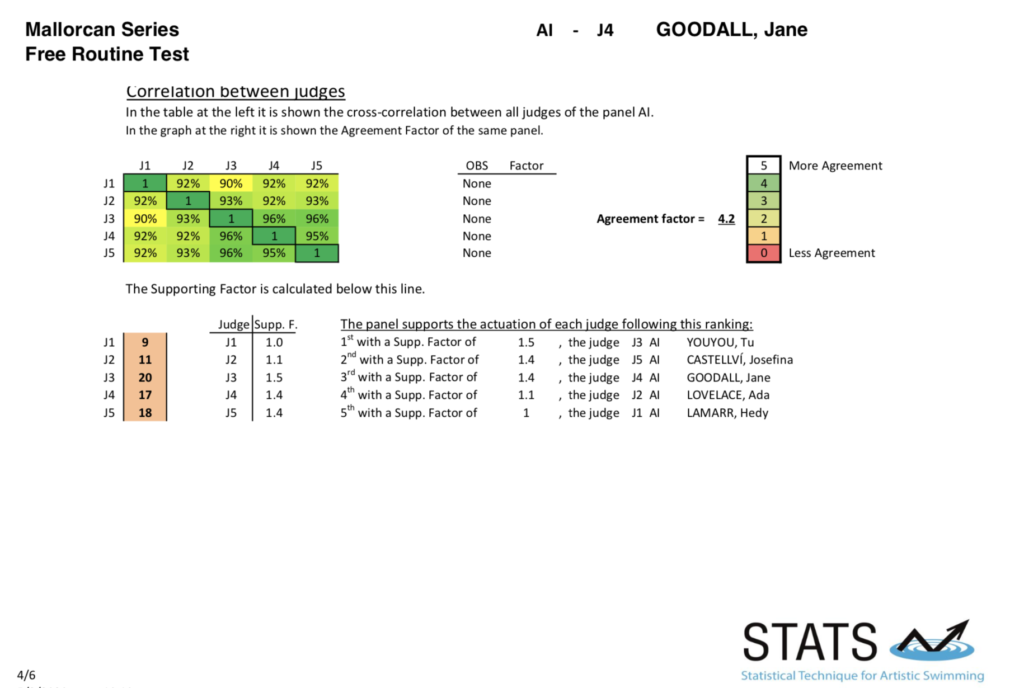

On top of giving a near-immediate feedback, STATS also monitors the agreement factor, and allows to see at a glance if the whole panel is looking for the same criteria in a routine. The analysis looks at the whole panel (agreement factor), but also at each judge’s performance within the same panel (supporting factor).

“Judges have to agree on what is best, what is medium, and what is low performance,” Bilbao said. “That agreement factor is very important. Maybe you personally felt like you judged harshly or lower, but if the data says that we all had a lot of agreement, then we know we did well. We may not spend time discussing that. But if the agreement was low, then you never know where the truth is, and you have to talk about it immediately. You can even look for the judge who had the least agreement with you, and talk about why your scores were so different.”

In contrast, Palmer explained a too high or near-perfect number for the agreement factor is not wanted either, as it could mean that the panel came into the event with too many preconceived ideas.

“The scale goes from zero to five or six, more or less,” he said. “If we see an agreement factor above five, it means that maybe they all talked a bit too much at the beginning, or checked the scores of a previous meet. So, there was no observation, just assumptions.”

Readers can view two examples of full STATS reports at these links: one with a high (good) agreement factor, and one with a very low agreement factor.

Does STATS replace an evaluator?

No, STATS rather complements the work of the evaluator in international competitions. It also provides information for both evaluators and referees when planning and looking at a meet. After obtaining the agreement and supporting factors from the statistical analysis, the referees can make decisions on the spot if needed, like identifying who cannot be together, or modifying panels of judges during the competition.

“It also helps the evaluator identify what needs to be discussed right away,” Palmer said. “We sometimes lose a lot of time thinking about which scores we gave for this one swimmer, but maybe it wasn’t the big problem of the day. We have a hard time immediately seeing the bigger picture or trends clearly. But we only have 10 or 15 minutes to discuss, so STATS helps to focus and find the real problems.”

Bilbao, Ayala and Palmer all agreed that it is also difficult to obtain constructive feedback solely with a short debrief session or with the evaluator’s report. It does tell you how you did, but not so much why or how to improve. STATS gives judges an opportunity for self-evaluation. They can also see what needs to be addressed in priority without wasting time or energy, in busy competitions that can often be mentally grueling.

What has been the feedback so far?

STATS has been tried in Catalonian and Spanish competitions for the last four years, and has globally received positive feedback. The progression and accuracy in national judges has become clearly visible through the data. Palmer also presented his tool to many foreign judges and other members of the TASC at the World Series stops in Barcelona in 2019 and in Madrid in 2018.

“Those who understand it appreciate it very much,” Bilbao said. “Of course, we need to have enough time to explain how to read the data. Maybe the judges’ community needs some introduction to statistical science (laughs)! But I will strongly recommend using this tool. Evaluators may have a lot of information, but the judges themselves need to have immediate things.”

To fully take advantage of all STATS can provide, open-mindedness is key. Judges have to be willing to discuss, to face their own mistakes, and to recognize that maybe they are not always right and that there are different ways to look at things.

“It’s difficult because we are trying to change the minds of some judges,” Ayala said. “In general, people try to hide their scores. Some might even say, ‘That’s just what I saw and that’s how it is.’ I know it’s hard when you think you’re working well, but the data says that you actually didn’t do so well. But that’s what we need to learn and to become better judges.”

Now, the team hopes to continue promoting STATS amongst international judges and to implement it in more competitions, whether at the national or elite level.

“With STATS plus comments from the evaluator, a judge has all the information almost immediately,” Palmer said. “In a few minutes, you have a picture of what happened to you. You have the information at a glance of a whole event that could be three hours long. Obviously we don’t want to take the work of the evaluators. But to have a general view of what happened in less than one hour after a competition and to try to correlate it with your feelings after judging, that is something unique.”

Article by Christina Marmet

If you’ve enjoyed our coverage, please consider donating to Inside Synchro! Any amount helps us run the site and travel costs to cover meets during the season.